Não tenho ambições nem desejos.

Ser poeta não é uma ambição minha.

É a minha maneira de estar sozinho.

I’ve no ambitions or desires.

My being a poet isn’t an ambition.

It’s my way of being alone.

— Edwin Honig & Susan M. Brown [Trs]

O rio da minha aldeia não faz pensar em nada.

Quem está ao pé dele está só ao pé dele.

The river of my village makes no one think of anything.

Anyone standing alongside it is just standing alongside it.

— Edwin Honig & Susan M. Brown [Trs]

A beleza é o nome de qualquer coisa que não existe

Que eu dou às coisas em troca do agrado que me dão.

Beauty is the name for something that doesn’t exist,

A name I give things for the pleasure they give me.

— Edwin Honig & Susan M. Brown [Trs]

12 September 2009

03 September 2009

Jules Renard — Journal 1887-1910

On peut être poète avec des cheveux courts.

On peut être poète et payer son loyer.

Quoique poète, on peut coucher avec sa femme.

Un poète, parfois, peut écrire en français.

2 janvier. 1890

You can be a poet and still wear your hair short.

You can be a poet and pay your rent.

Even though you are a poet, you can sleep with your wife.

And a poet may even, at times, write proper French.

— Louise Bogan & Elizabeth Roget [Trs.]

Nous ne connaissons pas l'Au-delà parce que cette ignorance est la condition sine qua non de notre vie à nous. De même la glace ne peut connaître le feu qu'à la condition de fondre, de s'évanouir.

24 septembre. 1890

We are ignorant of the Beyond because this ignorance is the condition sine qua non of our own life. Just as ice cannot know fire except by melting, by vanishing.

— Louise Bogan & Elizabeth Roget [Trs.]

Qui sait si chaque événement ne réalise pas un rêve qu'on a fait, qu'a fait un autre, dont on ne se souvient plus, ou qu'on n'a pas connu?

Sans date. 1887

La nostalgie que nous avons des pays que nous ne connaissons pas n'est peut-être que le souvenir de régions parcourues en des voyages antérieures à cette vie.

20 juin. 1887

Ma tête biscornue fait péter tous les clichés.

8 août 1891

My mis-shapen head cracks through all the clichés.

— Louise Bogan & Elizabeth Roget [Trs.]

On peut être poète et payer son loyer.

Quoique poète, on peut coucher avec sa femme.

Un poète, parfois, peut écrire en français.

2 janvier. 1890

You can be a poet and still wear your hair short.

You can be a poet and pay your rent.

Even though you are a poet, you can sleep with your wife.

And a poet may even, at times, write proper French.

— Louise Bogan & Elizabeth Roget [Trs.]

Nous ne connaissons pas l'Au-delà parce que cette ignorance est la condition sine qua non de notre vie à nous. De même la glace ne peut connaître le feu qu'à la condition de fondre, de s'évanouir.

24 septembre. 1890

We are ignorant of the Beyond because this ignorance is the condition sine qua non of our own life. Just as ice cannot know fire except by melting, by vanishing.

— Louise Bogan & Elizabeth Roget [Trs.]

Qui sait si chaque événement ne réalise pas un rêve qu'on a fait, qu'a fait un autre, dont on ne se souvient plus, ou qu'on n'a pas connu?

Sans date. 1887

La nostalgie que nous avons des pays que nous ne connaissons pas n'est peut-être que le souvenir de régions parcourues en des voyages antérieures à cette vie.

20 juin. 1887

Ma tête biscornue fait péter tous les clichés.

8 août 1891

My mis-shapen head cracks through all the clichés.

— Louise Bogan & Elizabeth Roget [Trs.]

16 August 2009

Lines from 'Camera Lucida' by Roland Barthes (tr. Richard Howard), FSG, 1981.

What the Photograph reproduces to infinity has occurred only once: the Photograph mechanically repeats what could never be repeated existentially. (p. 4)

Whatever it grants to vision and whatever its manner, a photograph is always invisible: it is not it that we see. (p. 6)

In an initial period, Photography, in order to surprise, photographs the notable; but soon, by a familiar reversal, it decrees notable whatever it photographs. The "anything whatever" then becomes the sophisticated acme of value. (p. 34)

Ultimately, Photography is subversive not when it frightens, repels, or even stigmatizes but when it is pensive, when it thinks. (p. 38)

When we define the Photograph as a motionless image, this does not mean only that the figures it represents do not move; it means that they do not emerge, do not leave: they are anesthetized and fastened down, like butterflies. (p. 57)

Earlier societies managed so that memory, the substitute for life, was eternal and that at least the thing which spoke Death should itself be immortal: this was the Monument. But by making the (mortal) Photograph into the general and somehow natural witness of "what has been," modern society has renounced the Monument. A paradox: the same century invented History and Photography. But History is a memory fabricated according to positive formulas, a pure intellectual discourse which abolishes mythic Time; and the Photograph is a certain but fugitive testimony; so that everything, today, prepares our race for this impotence: to be no longer able to conceive duration, affectively or symbolically: the age of the Photograph is also the age of revolutions, contestations, assassinations, explosions, in short, of impatiences, of everything which denies ripening. (pp. 93-94)

Whatever it grants to vision and whatever its manner, a photograph is always invisible: it is not it that we see. (p. 6)

In an initial period, Photography, in order to surprise, photographs the notable; but soon, by a familiar reversal, it decrees notable whatever it photographs. The "anything whatever" then becomes the sophisticated acme of value. (p. 34)

Ultimately, Photography is subversive not when it frightens, repels, or even stigmatizes but when it is pensive, when it thinks. (p. 38)

When we define the Photograph as a motionless image, this does not mean only that the figures it represents do not move; it means that they do not emerge, do not leave: they are anesthetized and fastened down, like butterflies. (p. 57)

Earlier societies managed so that memory, the substitute for life, was eternal and that at least the thing which spoke Death should itself be immortal: this was the Monument. But by making the (mortal) Photograph into the general and somehow natural witness of "what has been," modern society has renounced the Monument. A paradox: the same century invented History and Photography. But History is a memory fabricated according to positive formulas, a pure intellectual discourse which abolishes mythic Time; and the Photograph is a certain but fugitive testimony; so that everything, today, prepares our race for this impotence: to be no longer able to conceive duration, affectively or symbolically: the age of the Photograph is also the age of revolutions, contestations, assassinations, explosions, in short, of impatiences, of everything which denies ripening. (pp. 93-94)

13 July 2009

Lines from 'Assumption' by Samuel Beckett

Then, when his work had been done and an angry lull was imminent, he whispered.

To avoid the expansion of the commonplace is not enough; the highest art reduces significance in order to obtain that inexplicable bombshell perfection. Before no supreme manifestation of Beauty do we proceed comfortably up a staircase of sensation, and sit down mildly on the topmost stair to digest our gratification: such is the pleasure of Prettiness. We are taken up bodily and pitched breathless on the peak of a sheer crag: which is the pain of Beauty.

In the silence of his room he was afraid, afraid of that wild rebellious surge that aspired violently towards realization in sound. He felt its implacable caged resentment, its longing to be released in one splendid drunken scream and fused with the cosmic discord. Its struggle for divinity was as real as his own, and as futile.

The process was absurd, extravagantly absurd, like boiling an egg over a bonfire.

He drugged himself that he might sleep heavily, silently; he scarcely left his room, scarcely spoke, thus denying even that rare transmutation to the rising tossing soundlessness that seemed now to rend his whole being with the violence of its effort. He felt he was losing, playing into the hands of the enemy by the very severity of his restrictions. By damming the stream of whispers he had raised the level of the flood, and he knew the day would come when it could no longer be denied. Still he was silent, in silence listening for the first murmur of the torrent that must destroy him.

After a timeless parenthesis he found himself alone in his room, spent with ecstasy, torn by the bitter loathing of that which he had condemned to the humanity of silence. Thus each night he died and was God, each night revived and was torn, torn and battered with increasing grievousness, so that he hungered to be irretrievably engulfed in the light of eternity, one with the birdless cloudless colourless skies, in infinite fulfillment.

They found her caressing his wild dead hair.

— Samuel Beckett

To avoid the expansion of the commonplace is not enough; the highest art reduces significance in order to obtain that inexplicable bombshell perfection. Before no supreme manifestation of Beauty do we proceed comfortably up a staircase of sensation, and sit down mildly on the topmost stair to digest our gratification: such is the pleasure of Prettiness. We are taken up bodily and pitched breathless on the peak of a sheer crag: which is the pain of Beauty.

In the silence of his room he was afraid, afraid of that wild rebellious surge that aspired violently towards realization in sound. He felt its implacable caged resentment, its longing to be released in one splendid drunken scream and fused with the cosmic discord. Its struggle for divinity was as real as his own, and as futile.

The process was absurd, extravagantly absurd, like boiling an egg over a bonfire.

He drugged himself that he might sleep heavily, silently; he scarcely left his room, scarcely spoke, thus denying even that rare transmutation to the rising tossing soundlessness that seemed now to rend his whole being with the violence of its effort. He felt he was losing, playing into the hands of the enemy by the very severity of his restrictions. By damming the stream of whispers he had raised the level of the flood, and he knew the day would come when it could no longer be denied. Still he was silent, in silence listening for the first murmur of the torrent that must destroy him.

After a timeless parenthesis he found himself alone in his room, spent with ecstasy, torn by the bitter loathing of that which he had condemned to the humanity of silence. Thus each night he died and was God, each night revived and was torn, torn and battered with increasing grievousness, so that he hungered to be irretrievably engulfed in the light of eternity, one with the birdless cloudless colourless skies, in infinite fulfillment.

They found her caressing his wild dead hair.

— Samuel Beckett

Labels:

Samuel Beckett

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

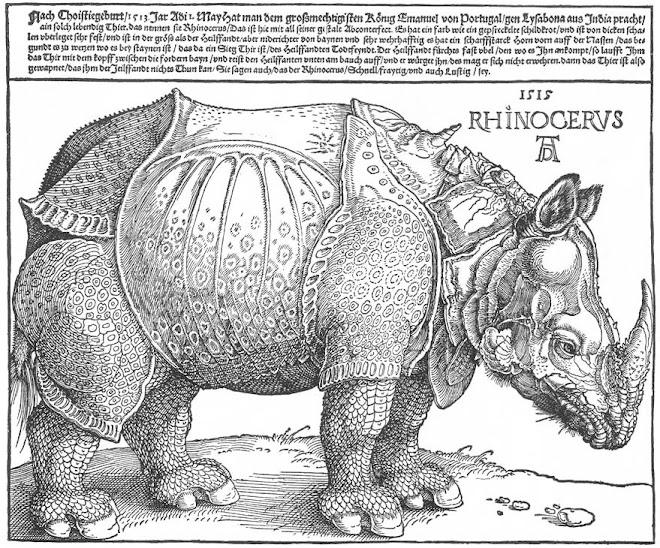

+--+Albrecht+D%C3%BCrer.bmp)